Did Lean fail?

It may appear that the ‘lean movement‘ failed, by and large. With hindsight, it’s wiser to conclude that Lean was hardly ever attempted.

Why didn’t more companies follow Toyota’s lead and get system-wide, coherent lean or flow systems in place? The problem is that while Toyota (and some other firms) show-cased a solution to rhythmic flow organization, the path to install such systems has been far less obvious.

Toyota itself was forthcoming about its TPS system, but the company was never great at describing exactly how they got where they were. This is a common denominator among BetaCodex pioneers. It took decades for practitioners like Taiichi Ohno and John Shook, for consultants and academics to produce proper codifications and interpretations of TPS and lean principles, and to make recommendations for transformation beyond the boring “It will take a very long time, and it will be very hard work, even if you stick to all the principles.”

Cohesive, practical transformation approaches remained utopian until recently. Worse: Consistent lean approaches and even “partial solutions” remained hard to grasp for most, even for industrial firms willing to mimic Toyota. One reason is that, to achieve batches of one (which have been a reality at Toyota for decades) will forever remain elusive in many industries and types of production like:

High-volume production – which is common in process industries and Fast-

Moving Consumer Goods industries. Think food, pharmaceuticals and toilet paper.High-Mix-Low-Volume industries or Mass Customization.

Think machine-building, furniture-making or medical devices production.

In both kinds of industrial settings, single-piece flow is impossible to achieve. This caused much shoulder shrugging and frustration, back in the 1980s and 1990s, when pretty much everybody in the West looked to Toyota for answers to the competitive crisis in industry. In the face of global competition, patience wore thin within the production and lean management communities. Instead of doing what Ohno did, dedicating 30 years and hard work to finding their own ways to produce a consistently lean system, most production experts and companies turned to lean tools and solutions, instead.

What we have come to call ‘lean‘ wasn’t lean at all, as it failed to be ‘transformational‘, pretty much entirely

Moving forward with tools and solutions, instead of taking the path of system-wide change turned out to be a cardinal mistake. In the short run, however, the quest

for silver bullets created a string of fads. Mechanistic patchwork approaches rose

to dominance in the lean management movement around the time of W. Edwards Deming’s death, in 1993, at least outside of Japan. Some of the fads, tools and quick fixes in the lean arena turned into genuine hits and into industries, brands and communities in their own right: Take Kaizen, Six Sigma, the so-called Theory of Constraints, or, more recently, Toyota Kata.

Worse: Tools and dabbling became synonymous with lean in the minds of business owners, managers, practitioners, consultants and academics alike. Bar systemic attempts and “system-wide changes” of the kind that Toyota under-took, the piecemeal approaches around lean were bound to fail, to fall short of expectations, or to fizzle away quickly. The tendency to “sell out” devastated large parts of the lean camp. To this day, the movement hasn’t recovered.

A few individuals and companies insisted on identifying suitable lean approaches capable of achieving flow:. Approaches that are sufficiently systemic to amount

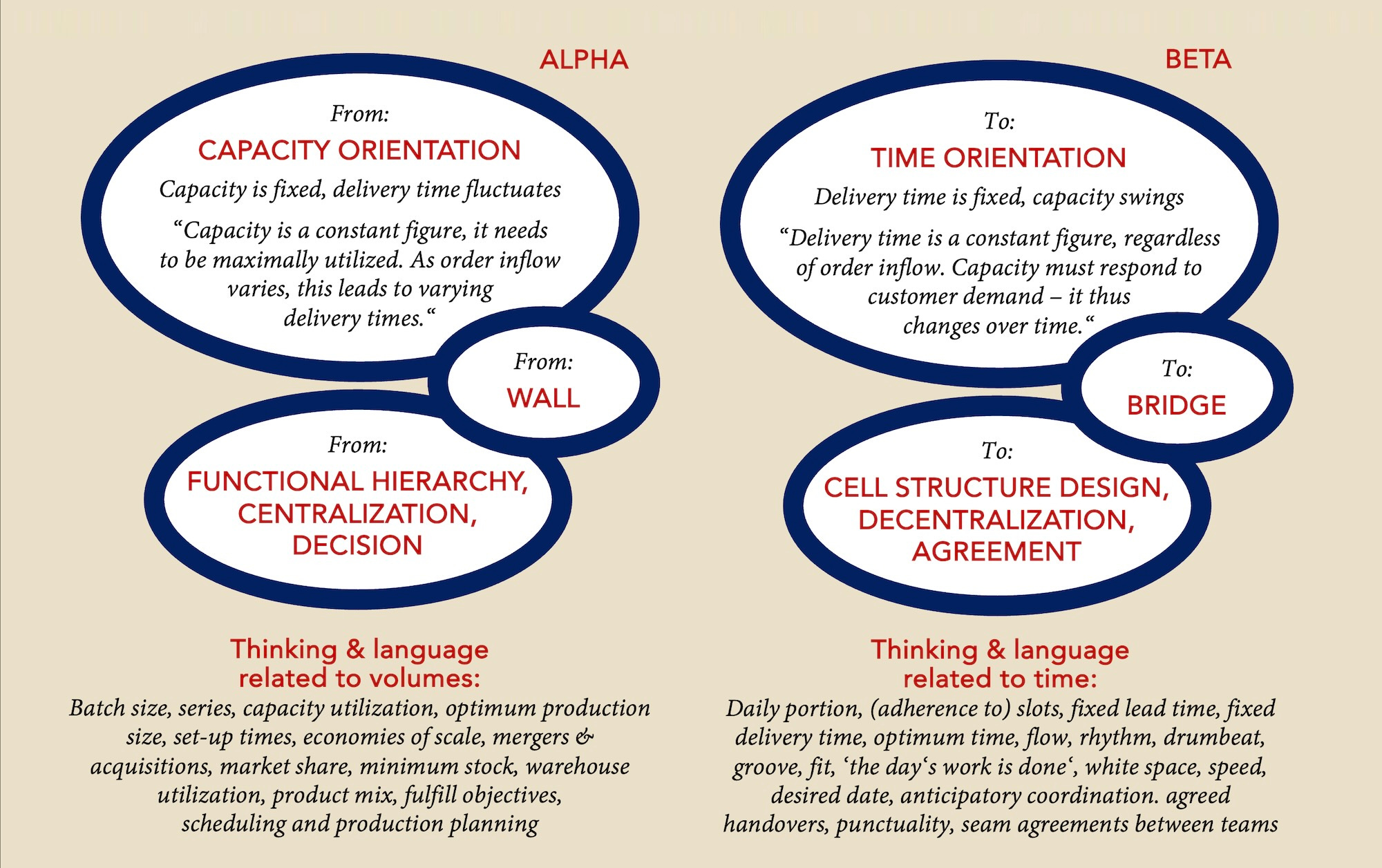

to more than dabbling. It is here where Time-Oriented Work Systems for industry come into play. What makes the “Big Three” approaches we talk about in the context of Time-Oriented Work Systems different is that they are not put in place within Alpha, or command-and-control systems, but that they are full-fledged alternatives to Alpha. The three approaches go by the names of Lean Repetitive Flexible Supply (Lean RFS), the Weichselbaum System and Quick Response Manufacturing (QRM). These approaches to lean are not fixes, but Beta systems designed for manufacturing sites, industrial production and industrial firms overall. In short: The Big Three, like TPS, are ways to overcome Alpha systems in favor of Beta systems. Overcoming the system is required to get adoption done: Starting from a logic of batches, steering, and functional division, an organization cannot optimize its way to rhythm and flow.

In manufacturing, overcoming batch logic is a necessary part of getting to rhythm and flow

Let’s talk about an enemy of time orientation first: Batch production. Batch production, or the grouping of products, with each batch going through the production process together. Batch production is a form of internal steering – which is a bad idea in complex (and thus dynamic) markets. See our white paper Organize for Complexity. Flow processes, on the other hand, are a way of leaving steering to the market, and having teams within the organization responding intelligently through “sense and respond”, allowing for pull to take hold. In complexity, this is both effective and will liberate people’s masteries and potential.

To put this into practice in High-Mix-Low-Volume production or mass customization, the Weichselbaum System uses the concept of the daily portion. Ernst Weichselbaum explains: “The biggest challenge is to throw out that assumption about ‘efficient production’, which is that producing large quantities is more efficient than small quantities or even one-off production. This assumption means that the customer must wait longer than is necessary. Plus: the larger or the more unnatural the batches, the more complicated the work scheduling and preparation. The ‘new batch size’ in a time-oriented approach, on the other hand, is typically one day's orders [of varied products] – what we call the daily portion. With such small batch sizes, big investments in complicated IT systems are no longer necessary; work preparation becomes simple and can take place daily, instead of consuming weeks. Planning can be eliminated entirely. Machines must be adapted to the optimum case of a ‘batch size of one’. To achieve this, minimizing set-up times is crucial.”

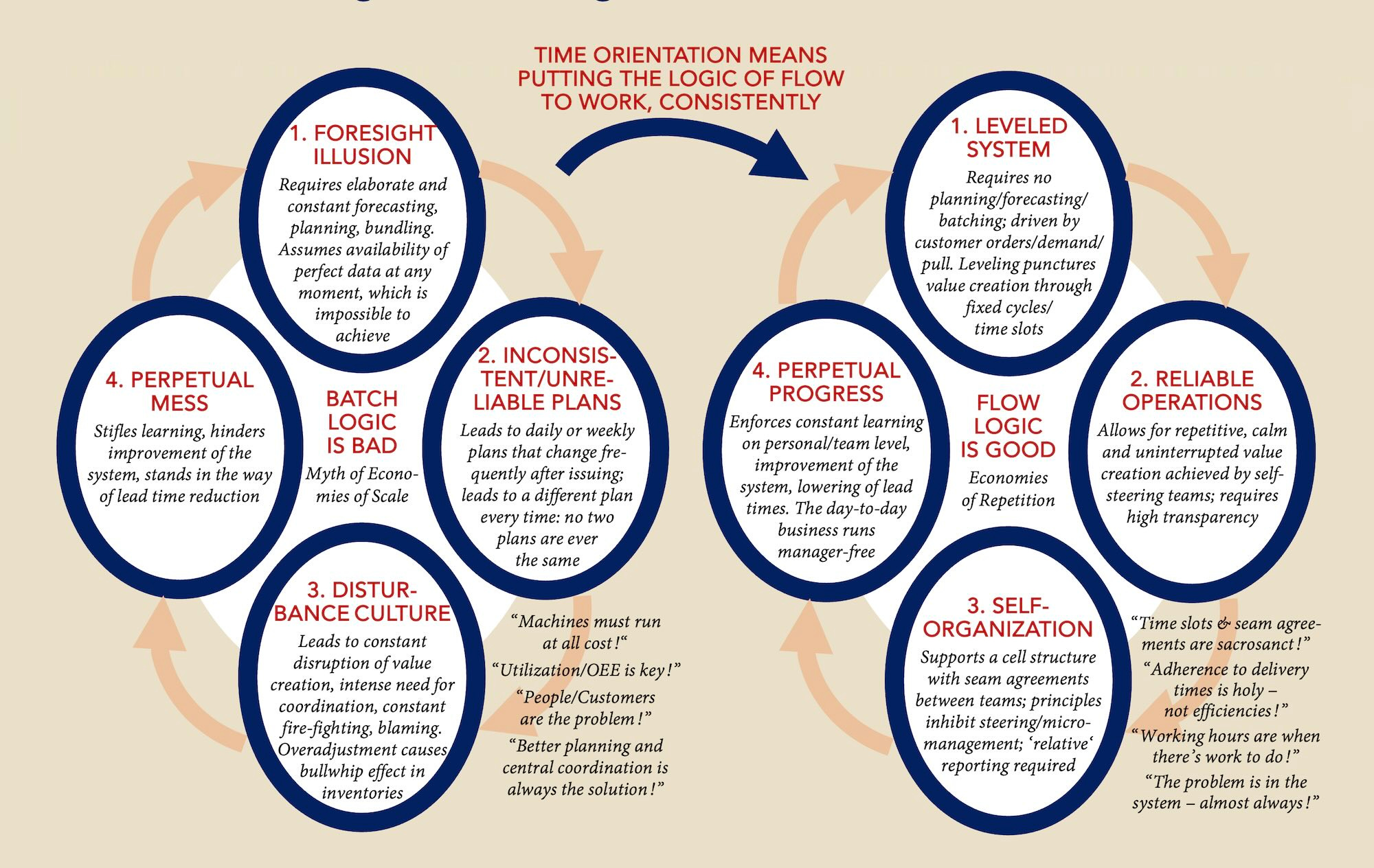

In industrial settings, time-orientation is the prerequisite for consistent self-organization and decentralization

If batches, steering and capacity orientation are bad ideas, then what does a time-oriented system look like, exactly? For industrial organizations, this means adopting time-oriented approaches and their underlying philosophy. Toyota adopted a time-oriented philosophy in its own way, inventing kanban in the process and arriving at single-piece-flow. Other companies adopted the Big Three approaches and arrived at rather different incarnations of time-oriented philosophy. The Weichselbaum approach probably goes farthest among the Big Three in being adamant that capacity cannot just swing, but that it must swing both upwards and downwards, if a production process is to be lastingly robust.

A few companies are lucky enough to thrive in their markets with a single product – everybody else must offer a huge range of products and variants. In the age of individual customer requirements and an exploding number of variants or models, it is much more customer-oriented and – viewed across an entire company – much more cost-effective to produce small quantities quickly than to produce large quantities slowly. This is why time-oriented organization is equally applicable to large volume production and low volume production. After all, serving market complexity is a greater good than ‘machine utilization’. A shift in philosophy is long over-due: From the neurotic anxiety of reducing complexity through steering to the peace of mind created by a system designed for today’s market complexity.

Time orientation is a different kind of organizational philosophy. It also uses a different kind of language, as you can see in the illustration.

The Big Three rhythmic lean approaches: How they stand out – why they are inevitable

In this paper, we will focus on the “Big Three” time-oriented work system approaches that, in addition to Toyota’s powerful take on single-piece flow, allow to realize time-orientation in all kinds of industries.

It is hard to appreciate the difference between the Big Three and other useful concepts related to time-oriented production systems, like Kanban or CONWIP, if we fail to acknowledge the difference between Optimizing the System and Overcoming the System. Put differently: In a sea of lean optimization with tools and solutions, the Big Three stand out in enabling, and in fact reinforcing systemic transformation.

They allow for fast adoption within days or weeks (not months or years), and, once adopted, provide sheer endless improvement potential

None of them requires large investments in IT or automation – to the contrary. They

may require small investments to improve settings or to acquire smaller machinery.They are systemic, whole-systems approaches that supplant Alpha systems of manufacturing, and affect all parts of an organization, including organizational structure and power dynamics: They require top management authorization.

They have proven their worth and practicality, having each been adopted for at least three decades, within at least dozens of companies.

They link philosophic principles and practices and are thus capable of producing “coherent” systems of organizing that are potentially long-lasting like Toyota’s.

They allow to systematically eliminate waste (like production planning and steering), reduce lead times, improve learning, and reduce functional division.

This article is an edited excerpt from the Slave to the Rhythm research paper.

For a comparison of the Big Three approaches, and for how to strengthen them with BetaCodex socio-tech, read the full BetaCodex research paper!